[ad_1]

After airing the suggestion a couple of months earlier, on 9 September 1929, Artistide Briand, French foreign minister, made a speech to the then 27 members of the League of Nations in which he proposed a federal union of European nations. He said: ‘among peoples who are geographically grouped together like the peoples of Europe there must exist a kind of federal link … Evidently the association will act mainly in the economic sphere … but I am sure also that from a political point of view, and from a social point of view, the federal link, without infringing the sovereignty of any of the nations taking part, could be beneficial’.

The idea of a United States of Europe met with a negative reaction from other European governments and the British press accused Briand of attempting to break links with the United States. In September 1930, the European members of the League effectively buried the scheme.

Plan of Union for Europe: the appearance and the reality of supposed ‘Federation’ idea

From our own Correspondent

12 July 1929

“A great scheme of M. Briand” is announced by M. Henri Bartde in the Œuvre to-day, and a great scheme, according to M.Barde’s description, it certainly is: nothing less, indeed, than the federation of Europe. M. Barde says that the information was given to him by M. Briand himself, whom he saw at the Quai d’Orsay yesterday. Nevertheless my own information enables me to say that the scheme is in fact – at any rate in its immediate intention – of a less ambitious and sensational character than Barde would suggest, and that its motive and aims are not exactly those which he gives.

Editorial: the United States of Europe

12 July 1929

M.Briand, apparently, is going to air suggestions for a European federation. It is to be economic at first, and then political. We cannot imagine what a European “economic federation” could mean unless it means Free Trade amongst the European countries. M. Briand is, if we are not mistaken, a member of the Pan-European League, of which Count Coudenhove-Kalergi is the founder. The literature of this League is an incessant, voluminous, and semi-lyrical outpouring, unrelated to any economic or political realities. If M. Briand has in mind anything that resembles the so-called ideas of these “Pan-Europeans” it will be impossible to take him seriously. But perhaps we do him an injustice. If he will, with the authority of the French Government behind him, champion general Free Trade (beginning, perhaps, by a lowering of European tariff walls) he will deserve the gratitude of mankind.

As for the political aspect of the matter, will M. Briand, again with the authority of the French Government behind him, urge that the military preponderance of the victors over the vanquished in the Great War be removed? That is the real political test, and what it amounts to, if carried out, is land disarmament, which, although. so much more urgent than naval disarmament, has not once been seriously attempted during all the years that hare passed since the end of the war. All we can do is to await Briand’s proposals with minds none the less open for being a little sceptical.

13 July 1929

M.Briand is not the first, nor will he be the last politician to make the phrase ‘United States of Europe’ serve some special and not disinterested political purpose. Yet the phrase is not meaningless, and some of its meaning may be present even in the mind of M.Briand. Twice in history has something akin to to the United States of Europe been achieved – the Roman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire. To neither of these is is a return possible in our own day.

United States of Europe: ‘one of M.Briand’s follies’

From our own Correspondent

11 September 1929

Paris

The Paris newspapers reflect a certain unanimity in their reactions to M. Briand’s Pan–Europa luncheon and to Dr. Stresemann’s speech delivered yesterday at Geneva. On the whole it is felt that M. Briand’s Pan-Europa scheme has proved a harmless diversion, whereas Dr. Stresemann’s speech is regarded as a diplomatic but candid avowal of a purely German point of view.

M. Briand’s supporters tend to be lyrical about his scheme but even they find it hard to seize upon any immediate and practical advantages such as are dear to the French political mind, while the newspapers of the extreme Right naturally dismiss the whole business frankly as folly and make joke about the excellent menu at M. Briand’s party. Similarly the attitude of the different newspapers toward Dr. Stresemann’s speech differs in the degree of their disapproval. But it is possible to detect some latent feeling underlying these different shades of opinion.

The Temps pours lukewarm praise over M. Briand’s Pan-Europa and commends a prudent decision to postpone carrying the matter any farther for another year. One must avoid indulging in facile delusions, says the Temps, but it is gratifying to see twenty-seven nations regarding such a scheme with sympathy.

Pertinax in the Echo de Paris, emerges from the events of the last few days positively bristling with epigrams and pins for every one of M. Briand’s air balloons of oratory. There were present, says Pertinax, at M.Briand’s luncheon representatives of twenty-seven nations, but as they were all either double or treble faced there seemed to be rather a crowd. He admitted the Pan-Europa scheme as one of M. Briand’s follies, and described the first appearance of Pan-Europa in public as “long-winded, vapid, and as elusive as a will-o’-the-wisp.”

The financial newspaper, L’Information devotes a leading article to statistics published by the British Board of Trade, and argues that Britain’s lack of enthusiasm for the idea of European federation is the natural result of the fact that she is becoming less and less interested in European markets. Recent trade returns, says L’Information, justify Britain in paying less attention to a possible federation of Europe than to the existing federation of British Dominions.

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

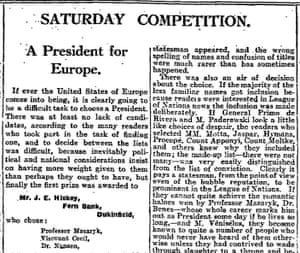

Saturday competition: choose a president for Europe

25 September 1929

Read the article in full.

United States of Europe – English and American objections

From our Correspondent

10 October 1929

Vienna, Wednesday

The former French Prime Minister, M. Edouard Herriot, delivered a lecture in Vienna last night on the subject of The United States of Europe. The meeting, which was presided over by the leader of the Pan-European movement, Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, lasted 1½ hours, and the ex-Prime Minister tried to explain the practical possibilities of a Pan-European solution to Europe’s problems such as had been proposed by M. Briand.

M. Herriot thought that the unity of Europe could be realised through analysis rather than through synthesis. The leading men of Europe, he said, must come together and attempt to eliminate the existing barriers. Many people were still opposed to the idea, but M. Herriot said they had not discovered that in the meantime the movement towards European unity had made great progress and that we were approaching its realisation, especially through economic means such as cartels and trusts.

There were, generally, three objections raised against the idea of a United States of Europe – namely, the American, the Russian, and the British objections. M. Herriot did not consider the American objection to be real because Senator Borah and others had assured M. Briand of their approval of his scheme. America had a cardinal interest in Europe’s recovery at as early a data as possible. Russia, which at present considered the scheme bourgeois, would gladly join in one a day, and as to England, M. Herriot expressed his conviction that Great Britain had no wish to oppose an European settlement. The proof of this contention was, said M. Herriot, that England was willing to participate in the coal inquiry at Geneva with proposals to solve this question from an all-European point of view. Naturally, the United States of Europe had to be created mainly on economic lines and should not touch the sovereignty of the various nations.

Editorial: The Union of Europe

18 July 1930

The British Government has been one of the last to reply to the Memorandum which M. Briand addressed to the European Powers last May inviting their consideration of his suggestions for what has been grandiloquently, and most misleadingly, described as a United States of Europe. The reply when it does come is of a “preliminary and tentative kind,” since the British Government has not had the opportunity to consult with the Governments of the Dominions. Nevertheless the British Government has felt no difficulty about expressing certain far-reaching criticism of M. Briand’s proposals.

Broadly, the British Note agrees with M. Briand’s aims and disagrees fundamentally with his methods. This disagreement is expressed with a clarity and decision which many will find refreshing. M. Briand’s aim is to divert European States from the barren contemplation of past enmities to constructive co-operation in the tasks of peace, especially in the economic field. That statement of time is not one to which anybody could take exception. It is a platitude. The only question is whether the machinery M. Briand suggests will have the effect which is desired or the opposite effect. The British Government holds that so far from diminishing it might actually tend to increase confusion and rivalry not only in Europe but in the world at large.

The reasons it gives for this criticism are not difficult to understand. The first and chief reason is that M. Briand proposes to set up an organisation independent of the League of Nations to do what in essentially the League’s work. That is a fundamental objection, and it is surprising that it should not have occurred to M. Briand. Perhaps it did, for M. Briand was careful to argue that his proposed European Union ought to work in harmony with the League. Nevertheless what he actually proposed to set up was an organisation modelled on the League but entirely independent of it. There would be no organic connection whatever between the two bodies. It is an excellent thing that the British Government should have grasped this cardinal point and put it firmly in the forefront of its criticisms. If there is to be a Union of Europe it must be a union definitely subordinate to the wider union of the League.

Apart from that, is it desirable to organise an independent and exclusive European Union? The British Note points to the obvious danger that such an organisation might emphasise what it calls inter-continental rivalries, by which it apparently means European rivalry with the United States of America and with the British Commonwealth. This is another objection hardly less vital than the first. But it is not quite so easily established. Since nobody objects to the existence of the United States of America or of the British Commonwealth (which are on excellent terns with one another), why should not a third group be organised and remain in friendly relationship with the first two? There is, perhaps, no real reason why it should not. But in fact, all schemes of European union derive their chief strength from the notion that union would increase Europe’s power of resistance, especially to the economic domination of America. The appeal is almost exactly parallel to the appeal for tightening the economic union of the British Commonwealth, and is open to the same dangers and objections. In both cases there is an element of genuine idealism, and it is perfectly true that economic union within the Empire, as within Europe is a thing greatly to be desired.

There are one or two things which M. Briand could have said which might have led one to a different conclusion. But he was careful not to say them. He might have said that the basis of European union should be European disarmament, or European Free Trade. Either of these suggestions would have been a real contribution to the cause of peace. But he said that political questions came first and that economic progress must wait, like disarmament, upon security. There is, therefore, no change there. M. Briand is only saying what every French Foreign Minister has always said before the League of Nations. Still more sensationally, M. Briand might have argued that the time had come for European States to merge themselves in a truly federal system. That would have involved some sacrifice of their independence, and M. Briand was careful to say that sovereign rights most be retained intact. No true federation is therefore possible or even contemplated. Or M. Briand might have argued that it would be well to bring into his European system those semi-European States (Russia, and Turkey) which are not members of the League. But he declined to make even that small innovation. It is difficult, therefore, to find anything new or hopeful in his proposals. They have now been criticised from various angles by most of the leading European Powers, and it would be matter for neither surprise nor regret if the answer of the British Government led to their final abandonment before the next meeting of the League Assembly.

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

[ad_2]

READ SOURCE