A Danish retail chain selling everything from ornate stationery to painting utensils and soft furnishings is stepping up its UK expansion, making it a rare bright spot on a high street blighted by closures and rising costs.

Family-owned Søstrene Grene, nicknamed “the small Ikea” by some customers, has pulled forward a target of having 100 stores in the UK by three years following strong sales of the chain’s plethora of low-cost homewares, at a time when many British rivals are disappearing from view.

The company, founded in 1973 in Aarhus by a husband and wife team, initially aimed to reach 100 outlets by 2030, from 47 currently, but its popularity with British shoppers has given Mikkel Grene, chief executive and son of the founders, the conviction to hit that goal by 2027.

“We have decided to keep on investing quite heavily in physical stores — it is expensive — but we believe that if [stores] look and feel nice, the customers will also come — and we see that,” said Grene, the youngest of four siblings, who took the reins at 39, as the company opens a new flagship store near Oxford Street on Friday.

Søstrene Grene, pronounced suh-strahn-grah-nuh, translates to the Grene sisters and refers to Anna and Clara, two fictional characters inspired by family members, whom the chain uses to tell stories about the products. It sells £39.40 side tables and £3.54 candlesticks online and in stores in 17 countries including Germany, France and the Nordics.

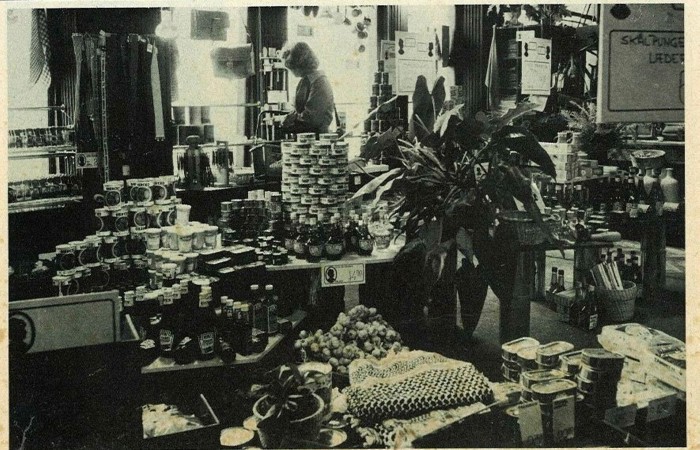

On a tour of the first ever Søstrene Grene in Aarhus, creative director Cresten Grene, points to the brown paint they use, “which makes it cosy”; classical music that plays in the background; and the labyrinth-like store layout that replicates “a treasure hunt” — a strategy that mirrors Ikea’s but at a much smaller scale.

Emily Scott, associate analyst at GlobalData said: “Compared to competitor Ikea, which also uses a maze design, Søstrene Grene offers a calmer, more pleasant atmosphere, through the use of lighting and music.”

The company’s UK growth is part of a wider plan to have 500 stores globally by 2027, up from 329 today. Its new flagship store in London represents the retailer’s largest investment in a UK shop to date.

The launch comes as the UK high street battles desultory consumer spending, higher borrowing costs and the shift to online shopping, and continues to reel from high-profile collapses such as Debenhams and House of Fraser that have left many buildings empty.

The UK lost 12,804 shops last year, according to PwC, equivalent to 35 closures a day. New store openings meant that on a net basis, 3,802 shops closed down — an improvement on the roughly 10,000 shops a year that shut in 2020 and 2021, but still a far higher number than the 2010 lows.

Retailers are also facing steep rises in costs from April as a result of the October Budget that are expected to lead to higher prices and fewer shops and jobs. Supermarkets J Sainsbury and Morrisons have already slashed some roles in response, while footwear chain Shoe Zone is closing stores because of it.

Kien Tan, a senior retail adviser at PwC, warned that retailers would “slow down rollouts” this year, too, as companies grapple with raises in employers’ national insurance contributions and the minimum wage.

“We can see it all over Europe, but especially in the UK,” Mikkel said, referring to a slow decline in high streets. “They literally roll out the red carpet when we open a store, they are really happy that somebody is actually going against the current.”

He admitted “the UK was a bumpy ride in the beginning”, having entered the market in 2016. “It was really expensive, now we can actually [afford] the rent.”

Graham Barr, head of UK retail at real estate firm CBRE, said rents had dropped “a little bit” since the Covid-19 pandemic, lowering the barrier to entry and benefiting chains such as Søstrene Grene.

However, the cost of opening shops in the UK has almost doubled in some cases since it entered the UK, Mikkel said, partly due to fit out expenses — Søstrene Grene uses a lot of wood and furniture to display and store its products. The brothers are not prepared to compromise on store aesthetics, an influence from their parents, which they believe helps sales.

Tan at PwC cautioned that despite their intentions “everybody is chasing after the same locations”, which could prevent Søstrene Grene from achieving its openings goal on time. He added: “Some chains have become unstuck as they got more mature — some of the locations you would think were really good, were not, and they were actually losing footfall.”

Mikkel said the company has “always been really careful with our expansion” and “we haven’t just started out with the big cities and expensive locations”.

In Manchester, for example, it opened “in a bit of a difficult location” five years ago. Although sales were disappointing at first, they have grown “20 to 25 per cent every year since and now it’s a really strong turnover and we can afford to move into the shopping mall and the nicer location”.

Søstrene Grene’s sales rose 22 per cent year-on-year to £247mn in 2024, while pre-tax profit was up 15 per cent to £24mn.

Mikkel was adamant that the group’s expansion was not a precursor to a sale or a possible stock market listing, nor do they want external investors.

“We still want to stay family-owned and operated,” he said. “We don’t know if there’s going to be another generation wanting to take over yet, because they are still too young, and it’s also very different taking over business with thousands of employees 1744356666, than when we started.”

“We do have the cash flow and also the help of the bank to finance it, so we have not been in a situation where there’s something that we really want to do, but we were not able to [get] the financing.”

The chain was founded by Inger and Knud Grene, who both hailed from entrepreneurial families. Their four children grew up in a “creative” household, according to the brothers.

Cresten initially wanted to be an architect but after moving to London and working in pubs for a few months he realised that “everything I had been searching for was at home”. Mikkel also thought he wanted to do something else but as soon as he started working in shops as a teenager, when the business only had a handful of employees, he changed his mind.

Cresten does not mind Søstrene Grene being likened to Ikea by some customers — “I have full respect for Ikea, they’ve been doing a tremendous job” — “but Søstrene Grene is hard to compare with anything”.