It was in late February of 1973 that I spent my first and only night in jail – and the experience was so surreal that it still speaks to me today, 50 years later.

With a group of leftwing friends I had ventured out into our city, Santiago, to splatter walls with slogans in support of the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. The midterm elections for Congress were coming up in early March. The rightwing opposition proclaimed that, if they received a supermajority, they would impeach Allende and put an end to his peaceful revolution, the first attempt in history to create a socialist society without the use of violence.

The words we had been enthusiastically daubing on a once-white wall close to the National Stadium were “A defender la democracia!” (to defend democracy). Because our democracy was in danger from conservatives conspiring to thwart the will of the people and stage an institutional coup.

We never got to complete those words on that wall. The kid who was supposed to be our lookout had fallen asleep and did not warn us that a police van was heading in our direction; a burly sergeant descended, followed by several daunting policemen.

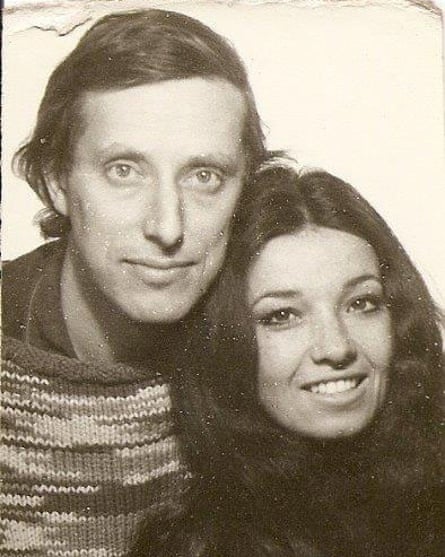

I was apprehensive. Now 30, in my student years I had fought men like these in street battles, gagged on their teargas, had even managed to elude a van similar to this one that had tried to ram me as I fled with my then girlfriend, Angélica, when we had protested against the US invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965. Years later, my friends and I were at their mercy again.

My apprehensions turned out to be unfounded. The sergeant gently informed us that we were under arrest, charged with vandalism and disturbing the peace. He seemed oddly paternal, as he and his men ushered us into the back of the van that would transport our group to the nearby police station. There, once again with the utmost courtesy, we were locked in a large cell already brimming with other pro-Allende supporters who had been caught that night.

Some of our fellow prisoners had been in this situation before and were not surprised that, instead of being beaten to a pulp, we were being treated in this considerate manner. It had been like that since Allende had won the presidency in 1970. The days when the national police force had maimed and killed activists were over.

And so, instead of nursing wounds, we spent the night discussing our young, nonviolent revolution until we were released in the morning with only an admonishment: we must not continue to deface public and private property.

As for the word we had been writing, “democracia”, it would remain forlorn and incomplete – like our democracy itself. Despite the dire economic situation caused by the US blockade of international aid, the Allende coalition received enough votes – 44.23% – to ward off impeachment.

Six months later, on 11 September 1973, the presidential palace was bombed and Allende was dead. All of those in that cell that night, and hundreds of thousands more, were fleeing for our lives as the democracy we had wanted to defend gave way to the 17 years of General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

What had been a utopian space for that one strange, luminous night, where the jailed could discuss the future without fear, soon became one more centre of terror. I have often wondered how many prisoners were smashed to the floor at that police station, how often electricity was applied to genitals, if it was a stop on the way to the nearby National Stadium where Allende supporters were tortured and executed in the days after the coup.

I recalled those special hours in that station often – in the days that followed the military takeover, when I went into hiding, and also when, 10 years later, I returned from exile. Not that I was able to avoid repression: there were beatings by soldiers in the street, teargassing during protests against the Pinochet regime, and I was deported from the country by plainclothes policemen. But I never spent another night in jail.

Over the years, the memory of those scant hours of serenity in that cell overflowing with hopeful militants and their dreams of a future of liberation remained strong. Over and over again, it flashed into my mind. When Chile’s democracy was restored in 1990, the police stations continued to be, especially for the young and the poor, sites of dread and injustice.

Worse was to come: during the massive protests that shook Chile to the core in 2019, enormous numbers of human rights violations by the police were registered by organisations such as Amnesty International. Eyes blinded, protesters shot and run over by police vans, thousands beaten, hundreds raped – assaults that recalled the grimmest days of the dictatorship.

Through it all, that spectral night in February 1973 continued to flicker as an alternative to the reality that humanity was living, offering me a light of hope in ever darker times, the certainty and promise that other models of behaviour and relationships could exist between law officers and the people they are supposed to be serving. I clung to that one brief interlude when police brutality vanished miraculously, replaced with civility in the dark and excessively sweet tea in the morning, something to be wished for everywhere.

Everywhere, because this is not only a story about faraway Chile. Day after day after day we witness violence against civilians in street after street, city after city, country after country, in and out of police stations, yesterday, today and, alas, tomorrow.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the coup that overthrew Allende, a man who saw law enforcement in a different light, a president who issued directives that saved me, my friends and countless others so we could give generously, and try to make the world a better place.

What pains me most is the terrible waste of resources and talent when the police, rather than acting as they did that night in Chile, unleash their fury on citizens, all the wondrous futures that are snuffed out. What my experience 50 years ago continues to fiercely and gently tell me, like a phantom that will not fade, is that it doesn’t need to be like this.