Archaeologists have found never-before-seen tattoos on the cheeks and arms of an 800-year-old Andean mummy, shedding more light on ancient cultural practices in South America.

Humans have adopted body modification methods throughout history to conform to prevalent beauty standards, social status and group affiliation, and even for ritual reasons. Among such body modifications, tattooing still exists as a widely practised cultural practice.

However, there are very few surviving examples of tattooed skin in archaeological records due to the soft nature of skin.

An analysis of existing records of preserved skin with evidence of tattoos suggests that South American coastal deserts have the most preserved tattooed human remains in the world.

So, scientists closely assessed a well-preserved female mummy held at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the University of Turin that had been excavated from a site in the Andes mountains.

Radiocarbon analysis revealed that the mummy was over 800 years old. She lived sometime between 1215 and 1382CE.

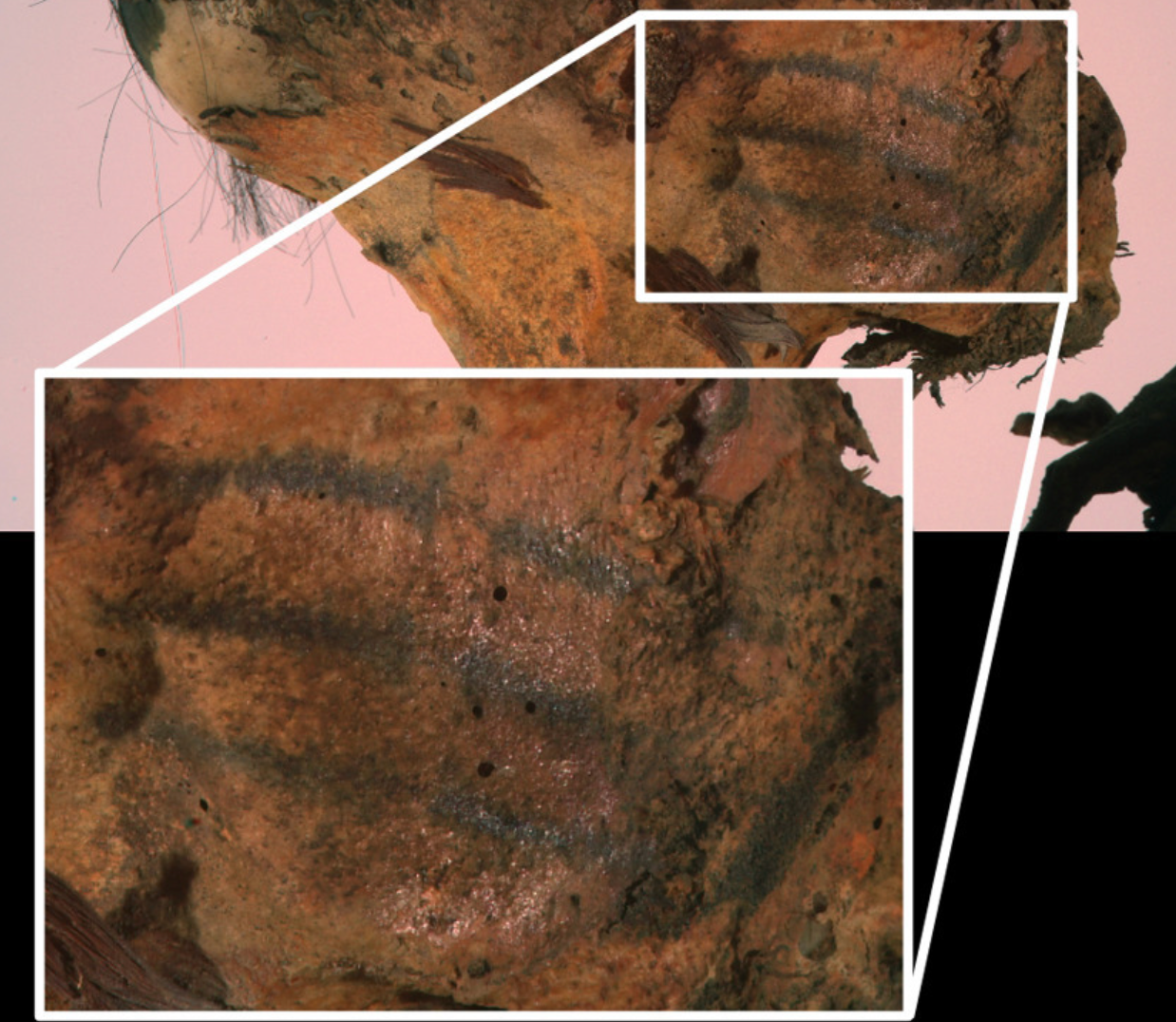

Researchers used two new infrared analysis techniques to look for any tattoos not visible to the naked eye. They were surprised to find tattoos on both cheeks of the mummy’s face, including three straight running lines from the ear to the mouth.

They also found a wrist tattoo in the shape of an S.

Using chemical analysis techniques like x-ray fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy, they determined the tattoos were made using pigments developed from the iron mineral magnetite and another called pyroxenes. The analysis revealed a surprising absence of charcoal, the most commonly used tattoo material reported in literature.

“The results show both rare shapes and anatomical location – lines on cheeks and S-like mark on wrist – and unusual ink composition,” they wrote in the study.

The simple tattoos have proved difficult to interpret and identify with any specific culture, however.

South American tattoos are typically more complex drawings on hands, wrists, forearms, and feet. Cheek tattoos are rarer. In fact, no other ancient tattoo found in the region so far is comparable to the “S” motif on the mummy’s arm.

Given the location of the tattoos on body parts not usually covered by clothing, researchers suspect they may have had a “decorative or communicative purpose”.

However, they add that “at the moment, it is not possible to attribute either a sort of medical or therapeutic purpose or a cultural provenance” to them.

“To conclude, the research actively contributes in the study of ancient tattoo practice, in particular in South America about eight centuries ago, and highlights the role of museum collections in the analysis of ancient cultures,” researchers noted.