[ad_1]

There is a film in this survey of the Hungarian artist Dóra Maurer that beguiles beyond all reasonable explanation. It consists of nothing but a sheet of white cloth, folded and unfolded in unceasing permutations. This occurs in near total darkness, the sheet appearing to transform itself as if by magic. Occasionally the screen splits, so that this beautiful origami doubles and redoubles, and sometimes a pair of hands becomes modestly visible. But that is all there is. The effect is mesmerising, nonetheless, and the more so for the irreducible simplicity of the film – screened on a sheet of white cloth.

Even without knowing much about the artist – and I freely confess that I did not – it is obvious that some kind of principle underpins the work. Perhaps it is mathematical: a sequence of rules played out with all the elegance of Fibonacci. Or perhaps it is to do with time: suspense builds, quite unexpectedly, as the moments pass. The experience slows everything down, a small mercy in the rush and thrum of Tate Modern; after a while, it doesn’t seem to matter if there is a meaning or method.

Dóra Maurer was born in Budapest in 1937. She works in almost every medium, from film and photography to painting, performance and sculpture. Her career began under communism, when the Hungarian government classified artworks as “supported”, “tolerated” or outright “prohibited”. Shows were shut down, artists threatened, art galleries suppressed. Maurer has said that her work is not overtly political, but it is very clearly a discreet form of defiance in its sheer experimentalism: worlds away from the regime’s preference for social realism and sentimental schlock.

What Can One Do With a Paving Stone, for instance, plays with gentle irony on the students’ ready weapon in the May 68 uprisings in Paris. Maurer is seen cradling, dragging, kissing and eventually hiding her stone in a harvest field somewhere in rural Hungary. It is 1971, and the performance feels necessarily secret, documented here in black-and-white photographs.

Likewise, she runs along the balcony of a block of flats in Budapest photographing another artist who is doing exactly the same thing, at the same time, on the opposite balcony. Dark and fugitive figures, they appear hauntingly human in the brutal cityscape.

Maurer might simply show a pair of hands going through various motions – pointing, signalling, flexing, subsiding in open-palmed fatigue. The modesty of the means contrasts with the rhetorical force of the actions, as if to suggest that even one person’s gestures might make a difference.

There was no market to speak of behind the iron curtain, for most of Maurer’s career, and thus no incentive to make expensive objects. But something in the spareness of her means speaks of the artist’s characteristic defiance. She used coils of old wire to make prints, pressing the paper down on the sharp and rusting metal, then shifting the ring so that the image evolved into gorgeous spirals. She filmed the shifting shadows contained in a cup. She even took the printing plate and folded it over and again, printing the effects in spectral grey ink so that it seems like a ghost of itself.

There is humour to her art, especially in the 70s, when Maurer was teaching to make a living, and working alongside other underground artists. Especially charming is Reversible and Changeable Phases of Movements No 3 from 1972, which could almost be a parody of the solemn conceptualism of the American and western European art scene of that time. Maurer photographed a man sitting on a chair, rising, standing, sitting, standing, mid-air and so on, in different sequences, until the seat is suddenly empty, the performer abruptly departed. He is depicted from behind, all the variations marked alongside like an algebraic sequence: the absurd mathematical relationship of a bottom and a chair.

Not all of the work is so compelling. The more she proceeds by systems, the drier the work tends to be. A number of mirrors are divided into ever smaller slices and hung from the ceiling to disrupt our vision of reality; except that they only draw attention to themselves. Folding, adjusting or slightly rearranging lines, twigs or blocks of colour according to numbers may be exactingly minimal but the pleasures are slender, in every respect.

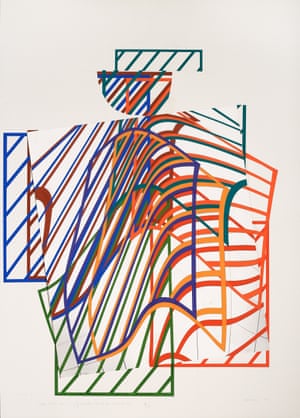

But in the 80s, Maurer began to make what she calls her Space Paintings, and these are both rich and original. Planes of colour speed and shift along the walls, high-chrome skeins and grids shiver into the illusion of three dimensions, and sometimes it even looks as if the painting has been created on a curving surface.

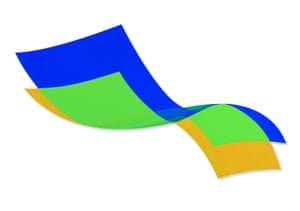

Most winning of all, in this show, is one of the works from her Overlappings series: 38, to be laconically precise, from 2007. Blue, yellow and green (or is it just blue and yellow, making green? – that’s the riddle), these fabulously undulating forms appear to flutter down the wall like sheets of paper dropped from a window and slowly descending on a summer’s breeze. The sight is all elation and freedom. Made in Hungary, but happening – as it seems – right here and right now, on the wall before you.

● At Tate Modern, London, until 5 July 2020

[ad_2]

READ SOURCE