[ad_1]

Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial piece of 70s art cinema, begins with an oil painting of a man on a red bed wearing just a T-shirt, flashing fleshy legs as his face explodes in inky smears. He’s in a room with a green carpet and yellow walls. For a few moments, Bertolucci shows just this portrait – of Lucian Freud by Francis Bacon – then a sensual jazz score slowly starts, and the film’s opening credits roll alongside this unmoving canvas. It is succeeded by a brutally dissected female figure sitting on a wooden chair – another Bacon portrait, this time of Henrietta Moraes. Eventually, the two paintings are seen side by side. Then we cut to Marlon Brando in a camel overcoat on a Paris bridge, yelling: “Fucking God!”

Behind Bertolucci’s eerie use of these oil paintings is the shocking story of an art exhibition that gripped Paris, established Bacon as the great European artist he had always dreamt of being – and left a man dead in a hotel toilet. Bertolucci was so astounded by Bacon’s solo show at the Grand Palais – which opened in October 1971, just as he was preparing to make his film in the French capital – that he took Brando to see it. He urged the actor, he later recalled, to “compare himself with Bacon’s human figures because I felt that, like them, Marlon’s face and body were characterised by a strange and infernal plasticity”.

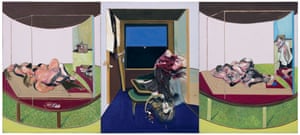

This unsettling quality did not limit itself to those two works. The seedily magnificent Three Figures in a Room, a triptych of two-metre-tall canvases painted in 1964, has enough infernal plasticity to fill anyone’s nightmares. On the left, a man sits naked on the toilet with his back to us. He seems to have no bones except for a line of vertebrae that poke out through his pink, orange and blue skin, which struggles to contain a spilling spread of relaxed muscle. The man’s buttocks fit like a plug into the white porcelain.

The first visitors to the hit retrospective had no idea how uncannily relevant this seven-year-old image was to Bacon’s private anguish. Three Figures in a Room was one of many paintings of the artist’s lover, George Dyer, that stole the show. But on 24 October, two days before the exhibition opened, staff at the Hôtel des Saints Pères found Dyer’s corpse slumped on the toilet. He died from a deliberate overdose.

The peculiar impact Bacon’s art made in Paris, and the violent death that shadowed his success, made this exhibition the defining moment of his art and life. Its spectre is now returning to haunt Paris. This autumn, the Pompidou Centre is mounting a new Bacon blockbuster. It starts by revisiting the Grand Palais show and explores how, from that point until Bacon’s death in 1992, he meditated on Greek tragedy and modern poetry as he repeatedly painted triptychs in memory of Dyer.

It was Georges Pompidou, the cultured former president of France whose memorial is the much-loved arts centre, who officially opened the Grand Palais exhibition and was given a tour by Bacon. It’s hard to imagine former British PMs Harold Wilson or Ted Heath taking a similar interest in these outrageous paintings of the tragic human creature. Margaret Thatcher allegedly called Bacon “that man who paints those dreadful pictures”. But this was France. And Bacon and Paris were made for each other.

In this city, with its rich and sleazy avant-garde traditions going back to poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud in the 19th century, Bacon was seen in a completely different context from the grey and conservative Britain, where he’d made his name in the 1950s. Like his beloved friend Lucian Freud, he was adept at appealing to British taste with portraits that, however radical, were recognisable and so more acceptable to the sceptical postwar British audience than, say, the abstract American paintings he himself sneered at as “old lace”. But in Paris, the true modernity and extremity of his art needed no humanist veneer. In the city of sex and death, Bacon was completely at home.

A photograph of Bacon at the Grand Palais opening offers a glimpse of the French tradition of dirty modernism he so easily slid into. It shows him chatting to two white-haired surrealist painters, André Masson and Joan Miró. Such titans of the prewar Parisian scene were still alive in 1971 – but Masson connects us with a much earlier outrage. When the wealthy psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan bought Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World, he decided this almost anatomical painting of a woman’s sex organs should have a “cover”, just like erotic paintings in earlier ages.

So Masson painted a ghostly outline of Courbet’s nude on a wooden panel that slid over the then secret masterpiece. It’s an episode that typifies the way sex, preferably of a highly disreputable variety, was cherished as a subversive force by French artists, writers and intellectuals from Courbet to the surrealist movement to its epitaph in Last Tango in Paris. Bacon was intensely aware of this culture, which connected left-bank bookshops with fleapit hotels. His friend and model, the artist Isabel Rawsthorne, even had an affair with the decadent surrealist writer Georges Bataille, whose 1928 novel Story of the Eye climaxes with the eyeball of a murdered priest being used as a sex toy.

In short, Paris was ready for Bacon, and he gave it what it wanted. He included his own equivalent of The Origin of the World among the 100-plus paintings at the Grand Palais: Two Figures, which has the feel of a revelation. A door has opened on a dark bedroom where, on roughly painted white sheets, two naked men have been caught having sex. The man on top leers out of the painting as he and his companion enjoy themselves with animal abandon. It’s one of his greatest paintings, and it could be appreciated in Paris in a way that was still difficult for Britain in 1971.

However, it was Bacon’s more recent paintings that defined the show. The star of many of these was a small-time criminal from London’s East End who became Bacon’s lover in 1963. George Dyer came from such a habitually law-breaking family that he remembered his mother trying to rob his pocket money. But he was too “nice”, lamented Bacon, to be a successful criminal.

The artist could easily afford to keep Dyer out of trouble. Born in Dublin in 1909, Bacon didn’t see artistic success until he painted his wartime nightmare of twisted gargoyles, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. This was around 1944. By the 60s, with a string of screaming popes behind him, he was rich. Working in a tiny bedsit studio in Kensington, London, he spent his earnings on champagne, fine wines and seafood feasts for his Soho friends. Dyer became part of this slightly desperate bohemia. He went from being a good-looking, well-dressed, would-be gangster to a depressed and clingy alcoholic. As Picasso’s women had found, being a muse sucks.

And there was Dyer’s physique smeared all over the Grand Palais in blue, black and livid red. In the triptych Three Studies of the Male Back, Dyer sits naked in a swivel chair in front of a small, hand-held shaving mirror and a larger rectangular one. Two of the paintings in the triptych show his reflected face as he shaves: it is sharp and hooked, with slicked hair and eyes narrowed and turned away from us. Bacon famously based his popes on Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X – and this enigmatic face in a mirror echoes another Velázquez painting that was kept just a short stroll from Soho: Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery.

Dyer’s back in this triptych is a loose, curvaceous landscape of bone and flesh. It looks as if his skeleton is not joined together but floats independently: a shoulder blade, a spinal column, bulging out of skin that’s soft white and rose, or bruised grey. His neck is massive, his legs roly-poly, his muscles both soft and hard. It is an unabashedly erotic study of male beauty that takes direct inspiration from some of Bacon’s favourite works of art: the drawings of Michelangelo, in which the male back is similarly idolised.

Casually erudite references to Velázquez and Michelangelo go naturally with views of people on the toilet in Bacon’s art. He said his was a “gilded gutter life”, veering between luxury and squalor. That is also true of his paintings as they mix base details with subtle textures and colours, all in sumptuous canvases that echo the old masters. At the Grand Palais, he was striving for greatness, determined to secure a place in the pantheon of high art. He may have chatted to various famous artists at the opening, but there was only one living painter he really wanted to be compared with: Picasso.

Bacon’s critical champion in Paris, who wrote the key essay in the exhibition catalogue, was the surrealist writer Michel Leiris, who was also a close friend of Picasso. According to Leiris, there was a clear connection between the two artists. A 1936 Picasso canvas called Sleeping Nude Woman, which belonged to Leiris and is now in the Pompidou collection, reveals how the men shared a visceral, even obscene surrealism. Picasso distorts female anatomy at will to get a view of his model that’s sheer sensual graffiti. Bacon does the same in his views of Dyer. But he took on Picasso more directly in the years before his Paris show.

Realising that he couldn’t bid for the Spaniard’s crown unless he painted the female body, Bacon got in training. To help him prepare for his 1966 nude Henrietta Moraes, a work that would stun visitors to the Grand Palais, the hard-drinking photographer John Deakin took a series of “candid” pictures of her – including ones he sold around Soho, much to her amusement. The resulting painting is one of the greatest nudes of the 20th century – and a bizarrely empowering one. Moraes lies with her feet towards us on a bed, her hips majestic, her right arm slung back, her animal-mask face unmistakably echoing Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Bacon was bidding to be recognised for what he was: the most visionary painter of human beings since Picasso. He was not going to let a private tragedy spoil that. His relationship with Dyer was all but over. He had been giving his broken muse money to make up for the end of their affair. But it seems Dyer was eager to see so many paintings of himself on show in Paris, and they patched things up – briefly. When Dyer was discovered dead, Bacon’s friends worked with the French authorities to keep the suicide secret. The conspiracy was so effective that until 2016 Bacon’s biographers were repeating the fiction that he heard of the horror only on the day of the opening. He actually kept his cool for a full 36 hours before the launch, to save the show – and his career.

Was Dyer’s death intended as an act of sabotage, motivated by revenge? Or was the reason for his suicide pure grief? Bacon did go on to give Dyer his due, and more, in tragic paintings that return obsessively to that death in a Paris hotel, but there’s no need to sentimentalise him or his art to see his greatness. The truth is that when the news broke, this sad death seemed only to confirm the desolate, harrowing vision so powerfully laid bare at the Grand Palais.

Bacon, an avowed atheist, shows human life as pure animality. We’re bodies without souls. His modernism is pitiless. And at that momentous show in Paris in 1971, it thrust him into the pantheon of European art.

• Bacon en toutes lettres is at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, until 20 January.

[ad_2]

READ SOURCE