[ad_1]

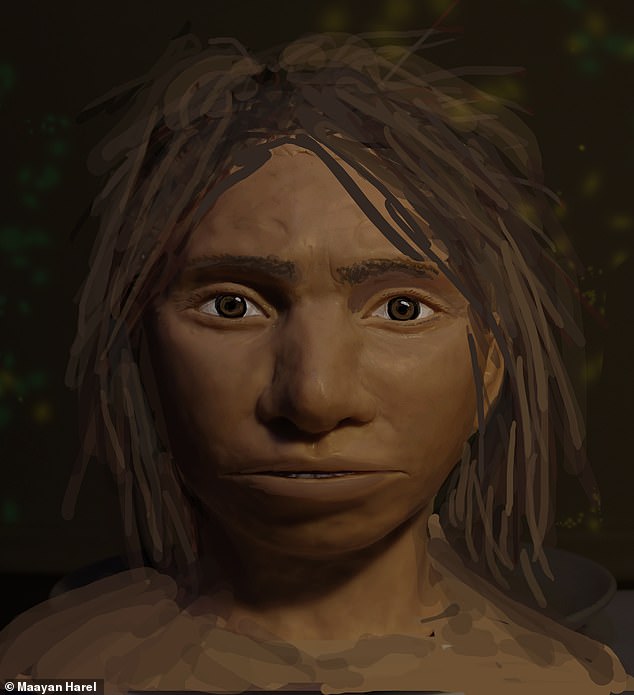

For the first time, scientists have reconstructed the face of Denisovans who lived alongside humans – and even interbred with them – some 100,000 years ago, before they went extinct.

The reconstructions are the first glimpse into what our elusive relatives actually looked like, given that everything we know about Denisovans comes from a single pinky bone, three teeth, and one lower jaw, found only in two caves in Asia.

Now, Israeli researchers have developed a new method of reconstructing fossils based on ancient DNA, and have used it to reveal the looks of our long-lost relatives.

They extracted the DNA from the little finger of a woman, who lived between 74 and 82 thousand years ago.

‘We provide the first reconstruction of the skeletal anatomy of Denisovans,’ says author Liran Carmel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

‘In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals, but in some traits, they resembled us, and in others they were unique.’

The first reconstruction of what ancient Denisovans looked like show that they resembled both humans and Neanderthals, but that they also had some unique features, such as a large dental arch and very wide skulls. This pictured reconstruction is of a juvenile female Denisovan who lived sometime between 82,000 and 74,000 years ago

The researchers identified 56 anatomical features in which Denisovans (left) differed from modern humans and/or Neanderthals (right), 34 of them in the skull. For example, Denisovans had wider skulls and longer jaws than Neanderthals

Denisovans are more related to Neanderthals than they are to humans. So, the team expected them to resemble Neanderthals.

The new reconstructions, based on DNA from a finger bone of a juvenile female who lived sometime between 82,000 and 74,000 years ago, now show Denisovans did indeed resemble Neanderthals, but they also shared features with humans.

And in some aspects, they were unique. For example, they had a large dental arch and very wide skulls.

‘We were particularly excited to find those anatomical traits where Denisovans differed from both modern humans and Neanderthals,’ Carmel told MailOnline.

DNA methylation, chemical modifications that influence gene activity without changing the underlying genetic sequence, can be used to reconstruct anatomical features, including some that do not survive in the fossil record. Here they were used to show what Denisovans (pictured) looked like

Overall, the researchers who reported their findings in the journal Cell, identified 56 anatomical features in which Denisovans differed from modern humans or Neanderthals, 34 of them in the skull.

To do so, they’ve used chemical modifications that influence gene activity without changing the underlying genetic sequence of As, Gs, Ts, and Cs, the so called DNA methylation.

The researchers first compared DNA methylation patterns between the three hominin groups to find regions in the genome that were differentially methylated.

Next, they looked for what those differences might mean for anatomical features based on what’s known about human disorders in which those same genes lose their function.

Earlier this year archaeologists discovered the first evidence of Denisovans – the ancient human ancestor that bred with humans – outside their small Siberian cave. Half a mandible – the jaw bone – found in a cave in China proved the extinct race populated the Tibetan Plateau around 160,000 years ago

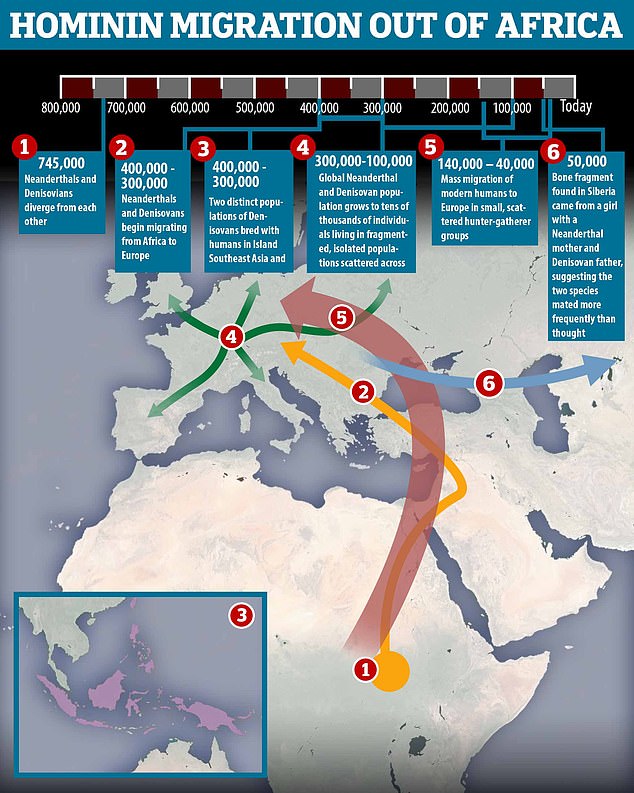

Between 300,000 and 100,000 years ago tens of thousands of Neanderthals and Denisovans lived in fragmented populations scattered around Europe and Asia

‘By doing so, we can get a prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change – for example, a longer or shorter femur,’ Gokhman says.

To test the method, the researchers first applied it to two species whose anatomy is known: the Neanderthal and the chimpanzee. They found that roughly 85% of the trait reconstructions were accurate in predicting which traits diverged and in which direction they diverged.

The findings show that DNA methylation can be used to reconstruct anatomical features, including some that do not survive in the fossil record. The approach may ultimately have a wide range of potential applications.

‘Studying Denisovan anatomy can teach us about human adaptation, evolutionary constraints, development, gene-environment interactions, and disease dynamics,’ Carmel says. ‘At a more general level, this work is a step towards being able to infer an individual’s anatomy based on their DNA.’

Denisovan remains have only been found in two places, in Denisova Cave in Russia’s Altai Mountains in Siberia (pictured) and in Baishiya Karst Cave in China

Both Denisovans and Neanderthals are thought to have interbred with humans, and some of us still carry their genes.

‘Denisovan DNA exists to this day in people of the pacific, Australia and East Asia – it can teach about how these admixture events affected modern humans,’ Liran told MailOnline.

‘We already know that these Denisovan DNA regions helped Tibetans to adapt to high altitude, and possibly Inuits to adapt to life in the arctic. There is definitely a lot more to be discovered with regard to how Denisovans shaped modern humans,’ Liran said.

[ad_2]

READ SOURCE